Sex manual - Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sex_manual

Early sex manuals

In the Graeco-Roman area, a sex manual was written by Philaenis of Samos, possibly a hetaira (courtesan) of the Hellenistic period (3rd–1st century BC). Preserved by a series of fragmentary papyruses which attest its popularity, it served as a source of inspiration for Ovid's Ars Amatoria, written around 3 BC, which is partially a sex manual, and partially a burlesque on the art of love.

Philaenis of Samos Wikipedia

Philaenis of Samos (in Greek, Φιλαινίς) was apparently a Greek courtesan of the 4th or 3rd centuries BC. She was commonly said to be the author of a manual on courtship and sex. The poet Aeschrion of Samos denied that his compatriot Philaenis was really the author of this notorious work.

Brief fragments of the manual, including the introductory words, have been rediscovered among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P.Oxy. 2891). It begins: “Philaenis of Samos, daughter of Ocymenes, wrote the following things for those wanting ... life ...”Adapted from the translation in the online catalogue Oxyrhynchus: A City and its Texts (see below)

External links

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (based on ancient references, predating the rediscovery of the fragments, and mistakenly stating that the work was a poem)

- Papyrus and description, part of the online exhibition Oxyrhynchus: A City and its Texts (The Egypt Exploration Society) http://www.papyrology.ox.ac.uk/POxy/VExhibition/scribes_scholars/philaenis.html

Ars Amatoria ("The Art of Love") Main article: Ars Amatoria

The Ars Amatoria is a didactic elegiac poem in three books which sets out to teach the arts of seduction and love. The first book is addressed to men and teaches them how to seduce women, the second, also to men, teaches one how to keep a lover. The third is addressed to women and teaches seduction techniques. The first book opens with an invocation to Venus in which Ovid establishes himself as a praeceptor amoris (1.17) a teacher of love. Ovid describes the places one can go to find a lover, like the theater, a triumph, which is thoroughly described, or arena, and ways to get the girl to take notice, including seducing her covertly at a banquet. Choosing the right time is significant as are getting into her associates' confidence. Ovid emphasizes care of the body for the lover. Mythological digressions include a piece on the Rape of the Sabine women, Pasiphae, and Ariadne. Book 2 invokes Apollo and begins with a telling of the story of Icarus. Ovid advises lovers to avoid giving too many gifts, keep up their appearance, hide affairs, complement her, and ingratiate themselves with slaves to stay on their lover's good side. The care of Venus for procreation is described as is Apollo's aid in keeping a lover; Ovid then digresses on the story of Vulcan's trap for Venus and Mars. The book ends with Ovid asking his "students" to spread his fame. Book 3, opens with a vindication of women's abilities and Ovid's resolution to arm women against his teaching in the first two books. Ovid gives women detailed instructions on appearance telling them to avoid too many adornments. He advises women to read elegiac poetry, learn to play games, sleep with people of different ages, flirt, and dissemble. Throughout the book, Ovid playfully interjects, criticizing himself for undoing all his didactic work to men and mythologically digresses on the story of Procris and Cephalus. The book ends with his wish that women will follow his advice and spread his fame saying Naso magister erat, "Ovid was our teacher".

Ovid's Ars Amatoria, Wikipedia

The Ars amatoria (English: The Art of Love) is an instructional book series elegy in three books by Ancient Roman poet Ovid. It was written in 2 AD. It is about teaching basic Gentlemanly male and female relationship skills and techniques.

Background Book one of Ars Amatoria was written to show a man how to find a woman. In book two, Ovid shows how to keep her. The third book, written two years after the first books were published, gives women advice on how to win and keep the love of a man ("I have just armed the Greeks against the Amazons; now, Penthesilea, it remains for me to arm thee against the Greeks...").

The Ars amatoria can be called a burlesque satire on didactic poetry.[citation needed] It claims: Aeacidae Chiron, ego sum praeceptor Amoris[1] ("As Chiron was to Achilles, so I am to Cupid"—in other words, "I pacified the wild Cupid"). Ovid offers advice to men on subjects such as, how to seduce and keep a woman, and also notably offers women advice on how to be attractive to men. He advises that, "if one is accompanying a lady to the horse-racing in the Circus Maximus, one should gallantly brush the dust from her gown. And if there isn't any dust there, brush it nonetheless. Also, "A young man should promise the moon to the object of his affections in letters—even a beggar can be rich in promises. A small woman, meanwhile, would be better advised to receive her suitor lying down ... but should make sure that her feet are hidden under her dress, so that her true size is not disclosed.".

Although Ovid protests Siqua fides arti, quam longo fecimus usu, / Credite: praestabunt carmina nostra fidem[2] ("If you trust art's promise that we've long employed / our songs will offer you their promise"), and his erotic advice indicates a supposed broad understanding of female psychology, in part he is following a literary tradition, especially the two previous exponents of the Latin love-elegy, Propertius and Tibullus, and the (mostly lost) erotic poetry of the Greek Hellenistic period.

Content The first two books, aimed at men, contain sections which cover such topics as 'not forgetting her birthday', 'letting her miss you - but not for long' and 'not asking about her age'. The third gives similar advice to women, sample themes include: 'making up, but in private', 'being wary of false lovers' and 'trying young and older lovers'. Although the book was finished around 2 AD, much of the advice he gives is applicable to any day and age. His intent is often more profound than the brilliance of the surface suggests. In connection with the revelation that the theatre is a good place to meet girls, for instance, Ovid, the classically educated trickster, refers to the story of the rape of the Sabine women. It has been argued that this passage represents a radical attempt to redefine relationships between men and women in Roman society, advocating a move away from paradigms of force and possession, towards concepts of mutual fulfilment.[3] The superficial brilliance, however, befuddles even scholars (paradoxically, Ovid consequently tended in the 20th century to be underrated as lacking in seriousness). The standard situations and cliches of the subject are treated in an entertainment-intended way, with details from Greek mythology, everyday Roman life and general human experience. Ovid likens love to military service, supposedly requiring the strictest obedience to the woman. He advises women to make their lovers artificially jealous so that they do not become neglectful through complacency. Perhaps accordingly, a slave should be instructed to interrupt the lovers' tryst with the cry 'Perimus' ('We are lost!'), compelling the young lover to hide in fear in a cupboard. Readers can follow the allusive chatter of the poet with a smile, without ever being able to be quite certain how seriously he means any of it. The tension implicit in this uncommitted tone is reminiscent of a flirt, and in fact, the semi-serious, semi-ironic form is ideally suited to Ovid's subject matter.

It is striking that through all his ironic discourse, Ovid never becomes ribald or obscene. Of course 'embarrassing' matters can never be entirely excluded, for alma Dione praecipite nostrum est, quod pudet, inquit, opus[4] '..."what you blush to tell", says nourishing Venus, "is the most important part of the whole matter"'. Sexual matters in the narrower sense are only dealt with at the end of each book, so here again, form and content converge in a subtly ingenious way. Things, so to speak, always end up in bed. But here, too, Ovid retains his style and his discretion, avoiding any pornographic tinge. The end of the second book deals with the pleasures of simultaneous orgasm. Somewhat atypically for a Roman, the poet confesses, Odi concubitus, qui non utrumque resolvunt. Hoc est, cur pueri tangar amore minus[5] ('I abhor intercourse which does not relieve both. This is also why I find less pleasure in the love of boys').

At the end of the third part, as in the Kama Sutra, the sexual positions are 'declined', and from them women are exhorted to choose the most suitable, taking the proportions of their own bodies into careful consideration. Ovid's tongue is again discovered in his cheek when his recommendation that tall women should not straddle their lovers is exemplified at the expense of the tallest hero of the Trojan Wars: Quod erat longissima, numquam Thebais Hectoreo nupta resedit equo[6] ('Because she was very tall, the Theban bride (Andromache) never sat on her Hectorian horse').

The polysemous word ars in the title is not, then, to be translated coldly as 'technique', but here really means 'art' in the sense of civilized refinement.

Appropriately for its subject, the Ars Amatoria is composed in elegiac couplets, rather than the dactylic hexameters, which are more usually associated with the didactic poem.

Reception The work was such a popular success that the poet wrote a sequel, Remedia Amoris (Remedies for Love). At an early recitatio, however, S. Vivianus Rhesus is noted as having walked out in disgust.[7] The assumption that the 'licentiousness' of the Ars amatoria was responsible in part for Ovid's relegation (banishment) by Augustus in AD 8 is dubious, and seems rather to reflect modern sensibilities than historical fact. For one thing, the Ars amatoria had been in circulation for eight years by the time of the relegation, and the book postdates the Julian Marriage Laws by eighteen years. Secondly, it is hardly likely that Augustus, after forty years unchallenged in the purple, felt the poetry of Ovid to be a serious threat or even embarrassment to his social policies. Thirdly, Ovid's own statement[8] from his Black Sea exile that his relegation was because of 'carmen et error' ('a song and a mistake') is, for many reasons, hardly admissible.

It is more probable that Ovid was somehow caught up in factional politics connected with the succession: Postumus Agrippa, Augustus' adopted son, and Augustus' granddaughter, Vipsania Julilla, were both relegated at around the same time. This would also explain why Ovid was not reprieved when Augustus was succeeded by Agrippa's rival Tiberius. It is likely, then, that the Ars amatoria was used as an excuse for the relegation.[9] This would be neither the first nor the last time a 'crackdown on immorality' disguised an uncomfortable political secret.

Legacy The Ars amatoria created considerable interest at the time of its publication. On a lesser scale, Martial's epigrams take a similar context of advising readers on love. Modern literature has been continually influenced by the Ars Amatoria, which has presented additional information on the relationship between Ovid's poem and more current writings.[10] The Ars Amatoria was included in the syllabuses of mediaeval schools from the second half of the 11th cent., and its influence on 12th and 13th cent. European literature was so great that the German mediaevalist and palaeographer Ludwig Traube dubbed the entire age 'aetas Ovidiana' ('the Ovidian epoch').[11] To this day, it has remained a topic of study in Latin literature classes in high schools and colleges around the world.

As in the years immediately following its publication, the Ars Amatoria has historically been victim of moral outcry. All of Ovid's works were burned by Savonarola in Florence, Italy in 1497; Christopher Marlowe's translation was banned in 1599, and another English translation of the Ars amatoria was seized by U.S. Customs in 1930.[12] Despite the actions against the work, Ars amatoria has remained a topic of study in Latin literature classes in high schools and colleges around the world.

It is possible that Edmond Rostand's fictionalized portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac makes an allusion to the Ars amatoria: the theme of the erotic and seductive power of poetry is highly suggestive of Ovid's poem, and Bergerac's nose, a distinguishing feature invented by Rostand, calls to mind Ovid's cognomen, Naso (from nasus, 'large-nosed').

References

Kamashastras Wikipedia

In Indian literature, Kāmashastra refers to the tradition of works on Kāma: love, erotics, or sensual pleasures. It therefore has a practical orientation, similar to that of Arthashastra, the tradition of texts on politics and government. Just as the former instructs kings and ministers about government, Kāmashastra aims to instruct the townsman (nāgarika) in the way to attain enjoyment and fulfillment.

The earliest text of the Kama Shastra tradition, said to have contained a vast amount of information, is attributed to Nandi the sacred bull, Shiva's doorkeeper, who was moved to sacred utterance by overhearing the lovemaking of the god Shiva and his wife Parvati. During the 8th century BC, Shvetaketu, son of Uddalaka, produced a summary of Nandi's work, but this "summary" was still too vast to be accessible. A scholar called Babhravya, together with a group of his disciples, produced a summary of Shvetaketu's summary, which nonetheless remained a huge and encyclopaedic tome. Between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, several authors reproduced different parts of the Babhravya group's work in various specialist treatises. Among the authors, those whose names are known are Charayana, Ghotakamukha, Gonardiya, Gonikaputra, Suvarnanabha, and Dattaka.

However, the oldest available text on this subject is the Kama Sutra ascribed to Vātsyāyana who is often erroneously called "Mallanaga Vātsyāyana". Yashodhara, in his commentary on the Kama Sutra, attributes the origin of erotic science to Mallanaga, the "prophet of the Asuras", implying that the Kama Sutra originated in prehistoric times. The attribution of the name "Mallanaga" to Vātsyāyana is due to the confusion of his role as editor of the Kama Sutra with the role of the mythical creator of erotic science. Vātsyāyana's birth date is not accurately known, but he must have lived earlier than the 7th century since he is referred to by Subandhu in his poem Vāsavadattā. On the other hand Vātsyāyana must have been familiar with the Arthashastra of Kautilya. Vātsyāyana refers to and quotes a number of texts on this subject, which unfortunately have been lost.

Following Vātsyāyana, a number of authors wrote on Kāmashastra, some writing independent manuals of erotics, while others commented on Vātsyāyana. Later well-known works include Kokkaka's Ratirahasya (13th century) and Anangaranga of Kalyanamalla (16th century). The most well-known commentator on Vātsyāyana is Jayamangala (13th century).

Philaenis of Samos Wikipedia

Philaenis of Samos (in Greek, Φιλαινίς) was apparently a Greek courtesan of the 4th or 3rd centuries BC. She was commonly said to be the author of a manual on courtship and sex. The poet Aeschrion of Samos denied that his compatriot Philaenis was really the author of this notorious work.

Brief fragments of the manual, including the introductory words, have been rediscovered among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri (P.Oxy. 2891). It begins: “Philaenis of Samos, daughter of Ocymenes, wrote the following things for those wanting ... life ...”Adapted from the translation in the online catalogue Oxyrhynchus: A City and its Texts (see below)

External links

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (based on ancient references, predating the rediscovery of the fragments, and mistakenly stating that the work was a poem)

- Papyrus and description, part of the online exhibition Oxyrhynchus: A City and its Texts (The Egypt Exploration Society) http://www.papyrology.ox.ac.uk/POxy/VExhibition/scribes_scholars/philaenis.html

Philaenis, The Art of Love: Early second century ADBeginning with techniques of seduction, the book is believed to have treated the sexual arts systematically, including descriptions of sexual positions, aphrodisiacs, abortifacients, and cosmetics. The rediscovery demonstrates that a real tradition of technical manuals underlay the more playful Art of Love written in Latin verse by Ovid in the late 1st century BC.

Well-heeled book-owners among the upper classes at Oxyrhynchus could get professional advice on matters of the heart from this well known manual on the ars amatoria which circulated widely in the ancient world. It is also one of the few technical works believed to have been written by a woman. Of Hellenistic date, her work was regarded as an authoritative guide for the voluptuary. She treated the art of love systematically, including descriptions of sexual positions, aphrodisiacs, abortifacients, and cosmetics. We know her text only from this papyrus fragment of a professionally produced book written in a fair-sized book hand, and preserving the beginning of the work (or an epitome of it): Fr. 1 col. 1, lines 1-4:

‘Philaenis of Samos, daughter of Okymenes wrote the following things for those wanting ... life ...’

The beginning is reminiscent of the opening of Herodotus’ Histories. Philaenis, however, begins with ‘How to Make Passes’ (peri peirasmon), then a section on seduction through flattery (‘say that he or she is “godlike”...isotheon’), followed by a section on kissing (peri philemat[on]). The style was simple, the treatment summary and matter of fact. The work represents the technical prose tradition on which Ovid drew in his elegiac didactic poem Ars Amatoria.

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri vol. XXIX no. 2891

Ars Amatoria ("The Art of Love") Main article: Ars Amatoria

The Ars Amatoria is a didactic elegiac poem in three books which sets out to teach the arts of seduction and love. The first book is addressed to men and teaches them how to seduce women, the second, also to men, teaches one how to keep a lover. The third is addressed to women and teaches seduction techniques. The first book opens with an invocation to Venus in which Ovid establishes himself as a praeceptor amoris (1.17) a teacher of love. Ovid describes the places one can go to find a lover, like the theater, a triumph, which is thoroughly described, or arena, and ways to get the girl to take notice, including seducing her covertly at a banquet. Choosing the right time is significant as are getting into her associates' confidence. Ovid emphasizes care of the body for the lover. Mythological digressions include a piece on the Rape of the Sabine women, Pasiphae, and Ariadne. Book 2 invokes Apollo and begins with a telling of the story of Icarus. Ovid advises lovers to avoid giving too many gifts, keep up their appearance, hide affairs, complement her, and ingratiate themselves with slaves to stay on their lover's good side. The care of Venus for procreation is described as is Apollo's aid in keeping a lover; Ovid then digresses on the story of Vulcan's trap for Venus and Mars. The book ends with Ovid asking his "students" to spread his fame. Book 3, opens with a vindication of women's abilities and Ovid's resolution to arm women against his teaching in the first two books. Ovid gives women detailed instructions on appearance telling them to avoid too many adornments. He advises women to read elegiac poetry, learn to play games, sleep with people of different ages, flirt, and dissemble. Throughout the book, Ovid playfully interjects, criticizing himself for undoing all his didactic work to men and mythologically digresses on the story of Procris and Cephalus. The book ends with his wish that women will follow his advice and spread his fame saying Naso magister erat, "Ovid was our teacher".

Ovid's Ars Amatoria, Wikipedia

The Ars amatoria (English: The Art of Love) is an instructional book series elegy in three books by Ancient Roman poet Ovid. It was written in 2 AD. It is about teaching basic Gentlemanly male and female relationship skills and techniques.

Background Book one of Ars Amatoria was written to show a man how to find a woman. In book two, Ovid shows how to keep her. The third book, written two years after the first books were published, gives women advice on how to win and keep the love of a man ("I have just armed the Greeks against the Amazons; now, Penthesilea, it remains for me to arm thee against the Greeks...").

The Ars amatoria can be called a burlesque satire on didactic poetry.[citation needed] It claims: Aeacidae Chiron, ego sum praeceptor Amoris[1] ("As Chiron was to Achilles, so I am to Cupid"—in other words, "I pacified the wild Cupid"). Ovid offers advice to men on subjects such as, how to seduce and keep a woman, and also notably offers women advice on how to be attractive to men. He advises that, "if one is accompanying a lady to the horse-racing in the Circus Maximus, one should gallantly brush the dust from her gown. And if there isn't any dust there, brush it nonetheless. Also, "A young man should promise the moon to the object of his affections in letters—even a beggar can be rich in promises. A small woman, meanwhile, would be better advised to receive her suitor lying down ... but should make sure that her feet are hidden under her dress, so that her true size is not disclosed.".

Although Ovid protests Siqua fides arti, quam longo fecimus usu, / Credite: praestabunt carmina nostra fidem[2] ("If you trust art's promise that we've long employed / our songs will offer you their promise"), and his erotic advice indicates a supposed broad understanding of female psychology, in part he is following a literary tradition, especially the two previous exponents of the Latin love-elegy, Propertius and Tibullus, and the (mostly lost) erotic poetry of the Greek Hellenistic period.

Content The first two books, aimed at men, contain sections which cover such topics as 'not forgetting her birthday', 'letting her miss you - but not for long' and 'not asking about her age'. The third gives similar advice to women, sample themes include: 'making up, but in private', 'being wary of false lovers' and 'trying young and older lovers'. Although the book was finished around 2 AD, much of the advice he gives is applicable to any day and age. His intent is often more profound than the brilliance of the surface suggests. In connection with the revelation that the theatre is a good place to meet girls, for instance, Ovid, the classically educated trickster, refers to the story of the rape of the Sabine women. It has been argued that this passage represents a radical attempt to redefine relationships between men and women in Roman society, advocating a move away from paradigms of force and possession, towards concepts of mutual fulfilment.[3] The superficial brilliance, however, befuddles even scholars (paradoxically, Ovid consequently tended in the 20th century to be underrated as lacking in seriousness). The standard situations and cliches of the subject are treated in an entertainment-intended way, with details from Greek mythology, everyday Roman life and general human experience. Ovid likens love to military service, supposedly requiring the strictest obedience to the woman. He advises women to make their lovers artificially jealous so that they do not become neglectful through complacency. Perhaps accordingly, a slave should be instructed to interrupt the lovers' tryst with the cry 'Perimus' ('We are lost!'), compelling the young lover to hide in fear in a cupboard. Readers can follow the allusive chatter of the poet with a smile, without ever being able to be quite certain how seriously he means any of it. The tension implicit in this uncommitted tone is reminiscent of a flirt, and in fact, the semi-serious, semi-ironic form is ideally suited to Ovid's subject matter.

It is striking that through all his ironic discourse, Ovid never becomes ribald or obscene. Of course 'embarrassing' matters can never be entirely excluded, for alma Dione praecipite nostrum est, quod pudet, inquit, opus[4] '..."what you blush to tell", says nourishing Venus, "is the most important part of the whole matter"'. Sexual matters in the narrower sense are only dealt with at the end of each book, so here again, form and content converge in a subtly ingenious way. Things, so to speak, always end up in bed. But here, too, Ovid retains his style and his discretion, avoiding any pornographic tinge. The end of the second book deals with the pleasures of simultaneous orgasm. Somewhat atypically for a Roman, the poet confesses, Odi concubitus, qui non utrumque resolvunt. Hoc est, cur pueri tangar amore minus[5] ('I abhor intercourse which does not relieve both. This is also why I find less pleasure in the love of boys').

At the end of the third part, as in the Kama Sutra, the sexual positions are 'declined', and from them women are exhorted to choose the most suitable, taking the proportions of their own bodies into careful consideration. Ovid's tongue is again discovered in his cheek when his recommendation that tall women should not straddle their lovers is exemplified at the expense of the tallest hero of the Trojan Wars: Quod erat longissima, numquam Thebais Hectoreo nupta resedit equo[6] ('Because she was very tall, the Theban bride (Andromache) never sat on her Hectorian horse').

The polysemous word ars in the title is not, then, to be translated coldly as 'technique', but here really means 'art' in the sense of civilized refinement.

Appropriately for its subject, the Ars Amatoria is composed in elegiac couplets, rather than the dactylic hexameters, which are more usually associated with the didactic poem.

Reception The work was such a popular success that the poet wrote a sequel, Remedia Amoris (Remedies for Love). At an early recitatio, however, S. Vivianus Rhesus is noted as having walked out in disgust.[7] The assumption that the 'licentiousness' of the Ars amatoria was responsible in part for Ovid's relegation (banishment) by Augustus in AD 8 is dubious, and seems rather to reflect modern sensibilities than historical fact. For one thing, the Ars amatoria had been in circulation for eight years by the time of the relegation, and the book postdates the Julian Marriage Laws by eighteen years. Secondly, it is hardly likely that Augustus, after forty years unchallenged in the purple, felt the poetry of Ovid to be a serious threat or even embarrassment to his social policies. Thirdly, Ovid's own statement[8] from his Black Sea exile that his relegation was because of 'carmen et error' ('a song and a mistake') is, for many reasons, hardly admissible.

It is more probable that Ovid was somehow caught up in factional politics connected with the succession: Postumus Agrippa, Augustus' adopted son, and Augustus' granddaughter, Vipsania Julilla, were both relegated at around the same time. This would also explain why Ovid was not reprieved when Augustus was succeeded by Agrippa's rival Tiberius. It is likely, then, that the Ars amatoria was used as an excuse for the relegation.[9] This would be neither the first nor the last time a 'crackdown on immorality' disguised an uncomfortable political secret.

Legacy The Ars amatoria created considerable interest at the time of its publication. On a lesser scale, Martial's epigrams take a similar context of advising readers on love. Modern literature has been continually influenced by the Ars Amatoria, which has presented additional information on the relationship between Ovid's poem and more current writings.[10] The Ars Amatoria was included in the syllabuses of mediaeval schools from the second half of the 11th cent., and its influence on 12th and 13th cent. European literature was so great that the German mediaevalist and palaeographer Ludwig Traube dubbed the entire age 'aetas Ovidiana' ('the Ovidian epoch').[11] To this day, it has remained a topic of study in Latin literature classes in high schools and colleges around the world.

As in the years immediately following its publication, the Ars Amatoria has historically been victim of moral outcry. All of Ovid's works were burned by Savonarola in Florence, Italy in 1497; Christopher Marlowe's translation was banned in 1599, and another English translation of the Ars amatoria was seized by U.S. Customs in 1930.[12] Despite the actions against the work, Ars amatoria has remained a topic of study in Latin literature classes in high schools and colleges around the world.

It is possible that Edmond Rostand's fictionalized portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac makes an allusion to the Ars amatoria: the theme of the erotic and seductive power of poetry is highly suggestive of Ovid's poem, and Bergerac's nose, a distinguishing feature invented by Rostand, calls to mind Ovid's cognomen, Naso (from nasus, 'large-nosed').

References

- ^ Ov, Ars am. 1,17

- ^ Ov, Ars am. 3,791–2

- ^ Dutton, Jacqueline, The Rape of the Sabine Women, Ovid Ars Amatoria Book I: 101-134, master's dissertation, University of Johannesburg, 2005

- ^ Ov, Ars am. 3,769

- ^ Ov, Ars am. 2,683

- ^ Ov, Ars am. 3,778

- ^ Agr. De art. am. 378-9

- ^ Ov. Tr., 2.207

- ^ F. Norwood (1964), 'The Riddle of Ovid's Relegatio', in Classical Philology. 58: 150-63

- ^ e.g. Gibson, R., Green, S., Sharrock, A., (eds.) 'The Art of Love: Bimillennial Essays on Ovid's Ars Amatoria and Remedia Amoris', OUP 2007; Sprung, Robert C., 'The Reception of Ovid's Ars Amatoria in the Age of Goethe', Senior Thesis, Harvard College, 1984.

- ^ McKinley, K.L., Reading the Ovidian Heroine, Brill, Leiden, 2001, xiii

- ^ Haight, A. L. and Grannis, C. B., Banned Books 387 BC to 1978 AD, R.R. Bowker & Co, 1978

- Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Ars Amatoria

- Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ars Amatoria

- An English translation of Amores and Ars Amatoria

- In Latin (book I) - In Latin (book II) . In Latin (book III)

- Poems by Ovid: Metamorphoses - Amores - Ars Amatoria - Remedia Amoris - Heroides - Fasti - Tristia - Epistulae ex Ponto - Ibis - Medicamina Faciei Femineae

Kamashastras Wikipedia

In Indian literature, Kāmashastra refers to the tradition of works on Kāma: love, erotics, or sensual pleasures. It therefore has a practical orientation, similar to that of Arthashastra, the tradition of texts on politics and government. Just as the former instructs kings and ministers about government, Kāmashastra aims to instruct the townsman (nāgarika) in the way to attain enjoyment and fulfillment.

The earliest text of the Kama Shastra tradition, said to have contained a vast amount of information, is attributed to Nandi the sacred bull, Shiva's doorkeeper, who was moved to sacred utterance by overhearing the lovemaking of the god Shiva and his wife Parvati. During the 8th century BC, Shvetaketu, son of Uddalaka, produced a summary of Nandi's work, but this "summary" was still too vast to be accessible. A scholar called Babhravya, together with a group of his disciples, produced a summary of Shvetaketu's summary, which nonetheless remained a huge and encyclopaedic tome. Between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, several authors reproduced different parts of the Babhravya group's work in various specialist treatises. Among the authors, those whose names are known are Charayana, Ghotakamukha, Gonardiya, Gonikaputra, Suvarnanabha, and Dattaka.

However, the oldest available text on this subject is the Kama Sutra ascribed to Vātsyāyana who is often erroneously called "Mallanaga Vātsyāyana". Yashodhara, in his commentary on the Kama Sutra, attributes the origin of erotic science to Mallanaga, the "prophet of the Asuras", implying that the Kama Sutra originated in prehistoric times. The attribution of the name "Mallanaga" to Vātsyāyana is due to the confusion of his role as editor of the Kama Sutra with the role of the mythical creator of erotic science. Vātsyāyana's birth date is not accurately known, but he must have lived earlier than the 7th century since he is referred to by Subandhu in his poem Vāsavadattā. On the other hand Vātsyāyana must have been familiar with the Arthashastra of Kautilya. Vātsyāyana refers to and quotes a number of texts on this subject, which unfortunately have been lost.

Following Vātsyāyana, a number of authors wrote on Kāmashastra, some writing independent manuals of erotics, while others commented on Vātsyāyana. Later well-known works include Kokkaka's Ratirahasya (13th century) and Anangaranga of Kalyanamalla (16th century). The most well-known commentator on Vātsyāyana is Jayamangala (13th century).

Etymology

Kaama (काम kāma) is a Sanskrit word that has the general meanings of "wish", "desire", and "intention" in addition to the specific meanings of "pleasure" and "(sexual) love".[1] Used as a proper name it refers to Kamadeva, the Hindu god of Love.List of Kamashastra works

Lost works

- Kâmashâstra of Nandi or Nandikeshvara. (1000)

- Vâtsyâyanasûtrasara, by the Kashmiri Kshemendra: eleventh-century commentary on the Kama Sutra

chapters

- Kâmashâstra, by Auddalaki Shvetaketu (500 chapters)

- Kâmashâstra or Bâbhravyakârikâ

- Kâmashâstra, by Chârâyana

- Kâmashâstra, by Gonikâputra

- Kâmashâstra, by Dattaka (according to legend, the author was transformed to a woman during a certain time)

- Kâmashâstra or Ratinirnaya, by Suvarnanâb

Medieval and modern texts

- Anangaranga, by Kalyanmalla

- Dattakasûtra, by King Mâdhava II of the Ganga dynasty of Mysore

- Janavashya by Kallarasa: based on Kakkoka's Ratirahasya

- Jayamangala or Jayamangla, by Yashodhara: important commentary on the Kama Sutra

- Jaya, by Devadatta Shâstrî: a twentieth-century Hindi commentary on the Kama Sutra

- Kâmasamuha, by Ananta (fifteenth century)

- Kama Sutra

- Kandarpacudamani

- Kuchopanishad or Kuchumâra Tantra, by Kuchumâra

- Kuchopanisad, by Kuchumara (tenth century)

- Kuttanimata, by the eighth-century Kashmiri poet Damodaragupta (Dāmodaragupta's Kuṭṭanīmata, though often included in lists of this sort, is really a novel written in Sanskrit verse, in which an aged bawd [kuṭṭanī] named Vikarālā gives advice to a young, beautiful, but as yet unsuccessful courtesan of Benares; most of the advice comes in the form of two long moral tales, one about a heartless and therefore successful courtesan, Mañjarī, and the other about a tender-hearted and therefore foolish girl, Hāralatā, who makes the mistake of falling in love with a client and eventually dies of a broken heart.)

- Mânasollâsa or Abhilashitartha Chintâmani by King Someshvara or Somadeva III of the Châlukya dynasty by Kalyâni A part of this encyclopedia, the Yoshidupabhoga, is devoted to the Kamashastra. (Manasolasa or Abhilashitachintamani) [1] [2]

- Nagarasarvasva or Nagarsarvasva, by Bhikshu Padmashrî, a tenth- or eleventh-century Buddhist

- Panchashâyaka, Panchasakya, or Panchsayaka, by Jyotirîshvara Kavishekhara (fourteenth century)

- Rasamanjari or Rasmanjari, by the poet Bhânudatta

- Ratikallolini, by Dikshita Samaraja

- Ratirahasya, by Kokkoka

- Ratimanjari, by the poet Jayadeva: a synthesis of the Smaradîpika by Minanatha

- Ratiratnapradîpika, by Praudha Devarâja, fifteenth-century Maharaja of Vijayanagara

- Shringararasaprabandhadîpika, by Kumara Harihara

- Smaradîpika, by Minanatha

- Samayamatrka, by Ksemendra

- Shrngaradipika, by Harihar

- Smarapradîpika or Smara Pradipa, by Gunâkara (son of Vachaspati)

- Sûtravritti, by Naringha Shastri: eighteenth-century commentary on the Kama Sutra

Kamashastra and Kāvya poetry

One of the reasons for interest in these ancient manuals is their intimate connection with Sanskrit ornate poetry (Kāvya). The poets were supposed to be proficient in the Kamashastra. The entire approach to love and sex in Kāvya poetry is governed by the Kamashastra.References

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. p. 66.

- The Complete Kama Sutra, Translated by Daniélou, Alain. ISBN 0-89281-492-6

The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana,

believed to have been written in the 1st to 6th centuries, has a

notorious reputation as a sex manual, although only a small part of its

text is devoted to sex. It was compiled by the Indian sage Vatsyayana

sometime between the second and fourth centuries CE. His work was based

on earlier Kamashastras or Rules of Love

going back to at least the seventh century BCE, and is a compendium of

the social norms and love-customs of patriarchal Northern India around

the time he lived. Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra is valuable today for

his psychological insights into the interactions and scenarios of love,

and for his structured approach to the many diverse situations he

describes. He defines different types of men and women, matching what he

terms "equal" unions, and gives detailed descriptions of many

love-postures.

The Kama Sutra was written for the wealthy male city-dweller.

It is not, and was never intended to be, a lover's guide for the masses,

nor is it a "Tantric love-manual". About three hundred years after the Kama Sutra

became popular, some of the love-making positions described in it were

reinterpreted in a Tantric way. Since Tantra is an all-encompassing

sensual science, love-making positions are relevant to spiritual

practice.

The Kama Sutra Wikipedia

The Kama Sutra (Sanskrit: कामसूत्र pronunciation (help·info), Kāmasūtra) is an ancient Indian Hindu[1][2] text widely considered to be the standard work on human sexual behavior in Sanskrit literature written by Vātsyāyana. A portion of the work consists of practical advice on sexual intercourse.[3] It is largely in prose, with many inserted anustubh poetry verses. "Kāma" which is one of the three goals of Hindu life, means sensual or sexual pleasure, and "sūtra"

literally means a thread or line that holds things together, and more

metaphorically refers to an aphorism (or line, rule, formula), or a

collection of such aphorisms in the form of a manual. Contrary to

popular perception, especially in the western world, Kama sutra is not

just an exclusive sex manual;

it presents itself as a guide to a virtuous and gracious living that

discusses the nature of love, family life and other aspects pertaining

to pleasure oriented faculties of human life.[4][5]

pronunciation (help·info), Kāmasūtra) is an ancient Indian Hindu[1][2] text widely considered to be the standard work on human sexual behavior in Sanskrit literature written by Vātsyāyana. A portion of the work consists of practical advice on sexual intercourse.[3] It is largely in prose, with many inserted anustubh poetry verses. "Kāma" which is one of the three goals of Hindu life, means sensual or sexual pleasure, and "sūtra"

literally means a thread or line that holds things together, and more

metaphorically refers to an aphorism (or line, rule, formula), or a

collection of such aphorisms in the form of a manual. Contrary to

popular perception, especially in the western world, Kama sutra is not

just an exclusive sex manual;

it presents itself as a guide to a virtuous and gracious living that

discusses the nature of love, family life and other aspects pertaining

to pleasure oriented faculties of human life.[4][5]

The Kama Sutra is the oldest and most notable of a group of texts known generically as Kama Shastra (Sanskrit: Kāma Śāstra).[6] Traditionally, the first transmission of Kama Shastra or "Discipline of Kama" is attributed to Nandi the sacred bull, Shiva's doorkeeper, who was moved to sacred utterance by overhearing the lovemaking of the god and his wife Parvati and later recorded his utterances for the benefit of mankind.[7]

Historians attribute Kamasutra to be composed between 400 BCE and 200 CE.[8] John Keay says that the Kama Sutra is a compendium that was collected into its present form in the 2nd century CE.[9]

Content

Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra has 1250 verses, distributed in 36 chapters, which are further organized into 7 parts.[10] According to both the Burton and Doniger[11] translations, the contents of the book are structured into 7 parts like the following:

1. General remarks: 5 chapters on contents of the book, three aims and priorities of life, the acquisition of knowledge, conduct of the well-bred townsman, reflections on intermediaries who assist the lover in his enterprises.

2. Amorous advances/Sexual union: 10 chapters on stimulation of desire, types of embraces, caressing and kisses, marking with nails, biting and marking with teeth, on copulation (positions), slapping by hand and corresponding moaning, virile behavior in women, superior coition and oral sex, preludes and conclusions to the game of love. It describes 64 types of sexual acts.

3. Acquiring a wife: 5 chapters on forms of marriage, relaxing the girl, obtaining the girl, managing alone, union by marriage.

4. Duties and privileges of the wife: 2 chapters on conduct of the only wife and conduct of the chief wife and other wives.

5. Other men's wives: 6 chapters on behavior of woman and man, how to get acquainted, examination of sentiments, the task of go-between, the king's pleasures, behavior in the women's quarters.

6. About courtesans: 6 chapters on advice of the assistants on the choice of lovers, looking for a steady lover, ways of making money, renewing friendship with a former lover, occasional profits, profits and losses.

7. Occult practices: 2 chapters on improving physical attractions, arousing a weakened sexual power.

In childhood, Vātsyāyana says, a person should learn how to make a living; youth is the time for pleasure, and as years pass one should concentrate on living virtuously and hope to escape the cycle of rebirth.[18]The Kama Sutra acknowledges that the senses can be dangerous: 'Just as a horse in full gallop, blinded by the energy of his own speed, pays no attention to any post or hole or ditch on the path, so two lovers, blinded by passion, in the friction of sexual battle, are caught up in their fierce energy and pay no attention to danger'(2.7.33).

Also the Buddha preached a Kama Sutra, which is located in the Atthakavagga (sutra number 1). This Kama Sutra, however, is of a very different nature as it warns against the dangers that come with the search for pleasures of the senses.

Many in the Western world wrongly consider the Kama Sutra to be a manual for tantric sex.[citation needed] While sexual practices do exist within the very wide tradition of Hindu Tantra, the Kama Sutra is not a Tantric text, and does not touch upon any of the sexual rites associated with some forms of Tantric practice.

Translations

The most widely known English translation of the Kama Sutra was privately printed in 1883. It is usually attributed to renowned orientalist and author Sir Richard Francis Burton, but the chief work was done by the pioneering Indian archaeologist, Bhagwanlal Indraji, under the guidance of Burton's friend, the Indian civil servant Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, and with the assistance of a student, Shivaram Parshuram Bhide.[19] Burton acted as publisher, while also furnishing the edition with footnotes whose tone ranges from the jocular to the scholarly. Burton says the following in its introduction:

A noteworthy translation by Indra Sinha was published in 1980. In the early 1990s its chapter on sexual positions began circulating on the internet as an independent text and today is often assumed to be the whole of the Kama Sutra.[21]

Alain Daniélou contributed a noteworthy translation called The Complete Kama Sutra in 1994.[22] This translation, originally into French, and thence into English, featured the original text attributed to Vatsyayana, along with a medieval and a modern commentary. Unlike the 1883 version, Alain Daniélou's new translation preserves the numbered verse divisions of the original, and does not incorporate notes in the text. He includes English translations of two important commentaries:

An English translation by Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar, an Indian psychoanalyst and senior fellow at Center for Study of World Religions at Harvard University, was published by Oxford University Press in 2002. Doniger contributed the Sanskrit expertise while Kakar provided a psychoanalytic interpretation of the text.[25]

Notes

References

External links

Sex manuals

Medieval sex manuals include the lost works of Elephantis, by Constantine the African; Ananga Ranga, a 12th century collection of Hindu erotic works; and The Perfumed Garden for the Soul's Recreation, a 16th century Arabic work by Sheikh Nefzaoui. The fifteenth-century Speculum al foderi (The Mirror of Coitus) is the first medieval European work to discuss sexual positions. Constantine the African also penned a medical treatise on sexuality, known as Liber de coitu.

Elephantis Wikipedia

Elephantis (fl. late 1st c. BC) was a Greek poetess apparently renowned in the classical world as the author of a notorious sex manual. Her works have not survived.

Works

According to Suetonius, the Roman Emperor Tiberius took a complete set of her works with him when he retreated to his resort on Capri.[1]

One of the poems in the Priapeia refers to her books:

And an epigram by the Roman poet Martial, which Smithers and Burton included in their collection of poems concerning Priapus, wrote:

She also wrote a manual about cosmetics and another about abortives.[5]

Notes

References

- Ian Michael Plant (2004). Women writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: an anthology. University of Oklahoma Press.

Ananga Ranga, Wikipedia

The Ananga Ranga (Stage of Love) or Kamaledhiplava (Boat in the Sea of Love) is an Indian sex manual written by Kalyana malla in the 15th or 16th century.[citation needed] The poet wrote the work in honor of Lad Khan, son of Ahmed Khan Lodi. He was related to the Lodi dynasty, which from 1451 to 1526 ruled from Delhi.[1] Later commentators have said it is aimed specifically at preventing the separation of a husband and wife. This work is often compared to the Kama Sutra, on which it draws.

Overview

It was translated into English in the year 1885, under the editorship of Sir Richard Francis Burton and consequently burnt by his wife Isabel Burton in the weeks following his death.

"Satisfaction and enjoyment comes for a man with possession of a beautiful woman. Men marry because of the peaceful gathering, love, and comfort and they often get nice and attractive women. But the men do not give the women full satisfaction The reason is due to the ignorance of the writings of the Kamashastra and the disdain of the different types of women. These men view women only from the perspective of an animal. They are foolish and spiritless".[2]

The work was intended to show that a woman is enough for a man. The book provides instructions in how a husband can promote the love for his wife through sexual pleasure. The husband can so greatly enjoy living with his wife, that it is as if he had lived with 32 different women. The increasingly varied sexual pleasures are able to produce harmony, thus preventing the married couple from getting tired of one another. In addition to the extensive catalogue of sexual positions for both partners, there are details regarding foreplay and lure.

The contents of the chapters of Burton's translation of the Ananga Ranga are as follows:

External links

Ratirahasya Wikipedia

The Ratirahasya (Sanskrit रतिरहस्य ) (translated in English as Secrets of Love, also known as the Koka Shastra) is a medieval Indian sex manual written by Kokkoka, a poet, who is variously described as Koka or Koka Pundit.[1][2][3][4] The exact date of its writing is not known, but it is estimated the text was written in the 11th or 12th century.[2] It is speculated that Ratirahasya was written to please a king by the name Venudutta. Kokkoka describes himself in the book as siddha patiya pandita, i.e. "an ingenious man among learned men".[1][5] The manual was written in Sanskrit.[6]

Unlike the Kama Sutra, which is an ancient sex manual related to Hindu literature, Ratirahasya deals with medieval Indian society. During the medieval age, India became more conservative compared to ancient India, freedom of women decreased, and premarital and extramarital sex were frowned upon. A sex manual was needed that would be suitable for the medieval cultural climate, and Ratirahasya was written, quite different from the ancient text Kama Sutra.[2]

There are fifteen pachivedes (chapters) and 800 verses in Ratirahasya which deal with various topics such as different physiques, lunar calendar, different types of genitals, characteristics of women of various ages, hugs, kisses, sexual intercourse and sex positions, sex with a strange woman, etc.[1][2] Kokokka describes various stages of love in Ratirahasya, the fifth stage being weight loss, the ninth is fainting, and the tenth and last stage is death.[7] Ratirahasya makes classifications of women, and describes erogenous zones and days that lead to women's easy arousal.

Ratirahasya is the first book to describe in detail Indian feminine beauty. The book classified women into four psycho-physical types, according to their appearance and physical features.[8][9]

According to W. G. Archer, Kokkoka "is concerned with how to make the most of sex, how to enjoy it and how to keep a woman happy."[2] In writing this text, Kokokka depended on a number of other authors including, among others Nandikeshvara, Gonikaputra, and Vatsyayana.[11]

Arabic, Persian and Turkish translations of the book are entitled Lizzat-al-Nissa.[12] Alex Comfort, author of The Joy of Sex, made an English translation of Ratirahasya in 1964 titled The Koka Shashtra, Being the Ratirahasya of Kokkoka, and Other Medieval Indian Writings on Love (London: George Allen and Unwin). Another English translation was made by S. C. Upadhyaya, entitled Kokashastra (Rati Rahasya) of Pundit Kokkoka. Some commentaries have been written on this text by Avana Rama Chandra, Kavi Prabhu, and Harihara. It is a popular text in India, second only to the Kama Sutra among sex manuals.[11]

A few translations of the ancient works were circulated privately, such as The Perfumed Garden….

In the late 19th Century, Ida Craddock wrote many serious instructional tracts on human sexuality and appropriate, respectful sexual relations between married couples. Among her works were The Wedding Night and Right Marital Living. In 1918 Marie Stopes published Married Love, considered groundbreaking despite its limitations in details used to discuss sex acts.

Theodoor Hendrik van de Velde's book Het volkomen huwelijk (The Perfect Marriage), published in 1926, was well known in Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Estonia. In Germany, Die vollkommene Ehe reached its 42nd printing in 1932 despite its being placed on the list of forbidden books, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, by the Roman Catholic Church. In Sweden, Det fulländade äktenskapet was widely known although regarded as pornographic and unsuitable for young readers long into the 1960s. In English, Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique has 42 printings in its original 1930 edition, and was republished in new editions in 1965 and 2000.

David Reuben, M. D.'s book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), published in 1969, was one of the first sex manuals that entered mainstream culture in the 1960s. Although it did not feature explicit images of sex acts, its descriptions of sex acts were unprecedentedly detailed, addressing common questions and misunderstandings Reuben had heard from his own patients. Most notably, Reuben dismissed popular medical-psychiatric notions of "vaginal" vs. "clitoral" orgasm, explaining exactly how female physiology works.

The Joy of Sex by Dr. Alex Comfort was the first visually explicit sex manual to be published by a mainstream publisher. Its appearance in public bookstores in the 1970s opened the way to the widespread publication of sex manuals in the West. As a result, hundreds of sex manuals are now available in print.

One of the currently most well known in America is The Guide to Getting it On by Paul Joannides. Now in its sixth edition, it has won several prestigious awards and been translated into 12 foreign languages since appearing in 1996.[1]

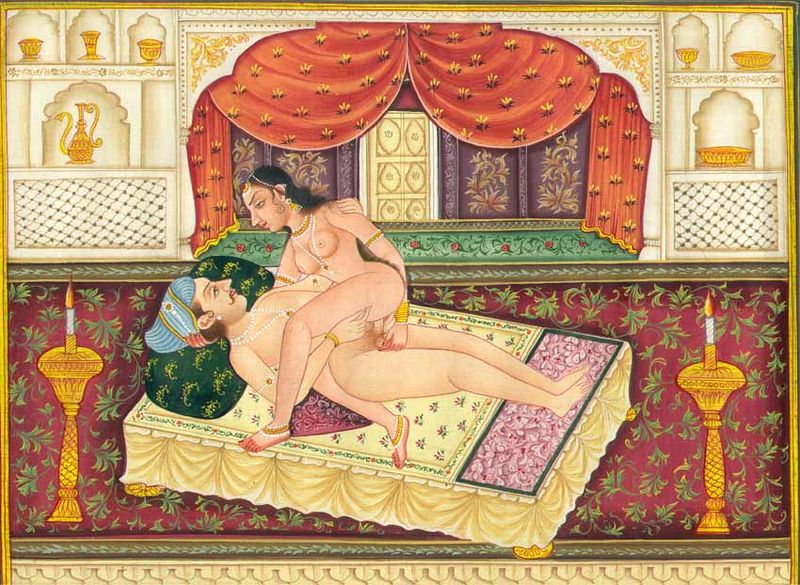

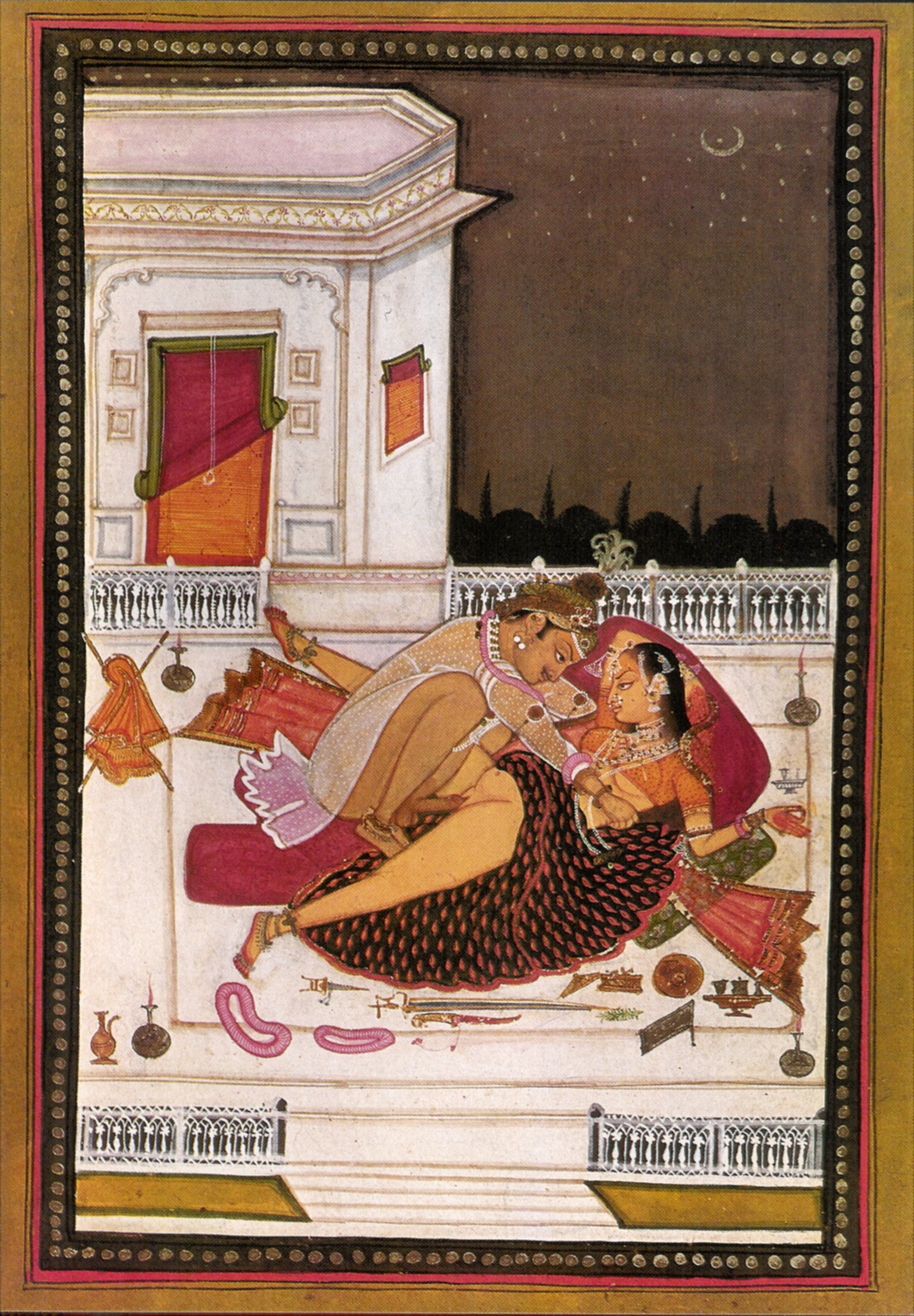

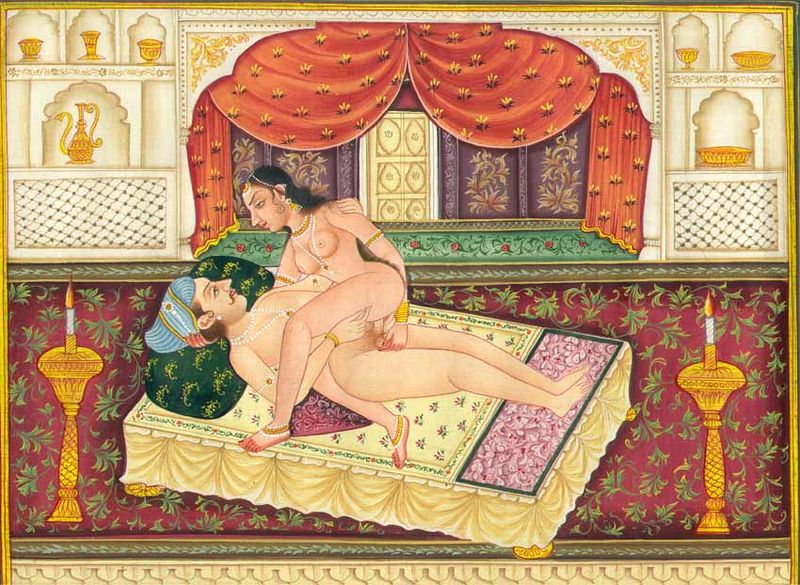

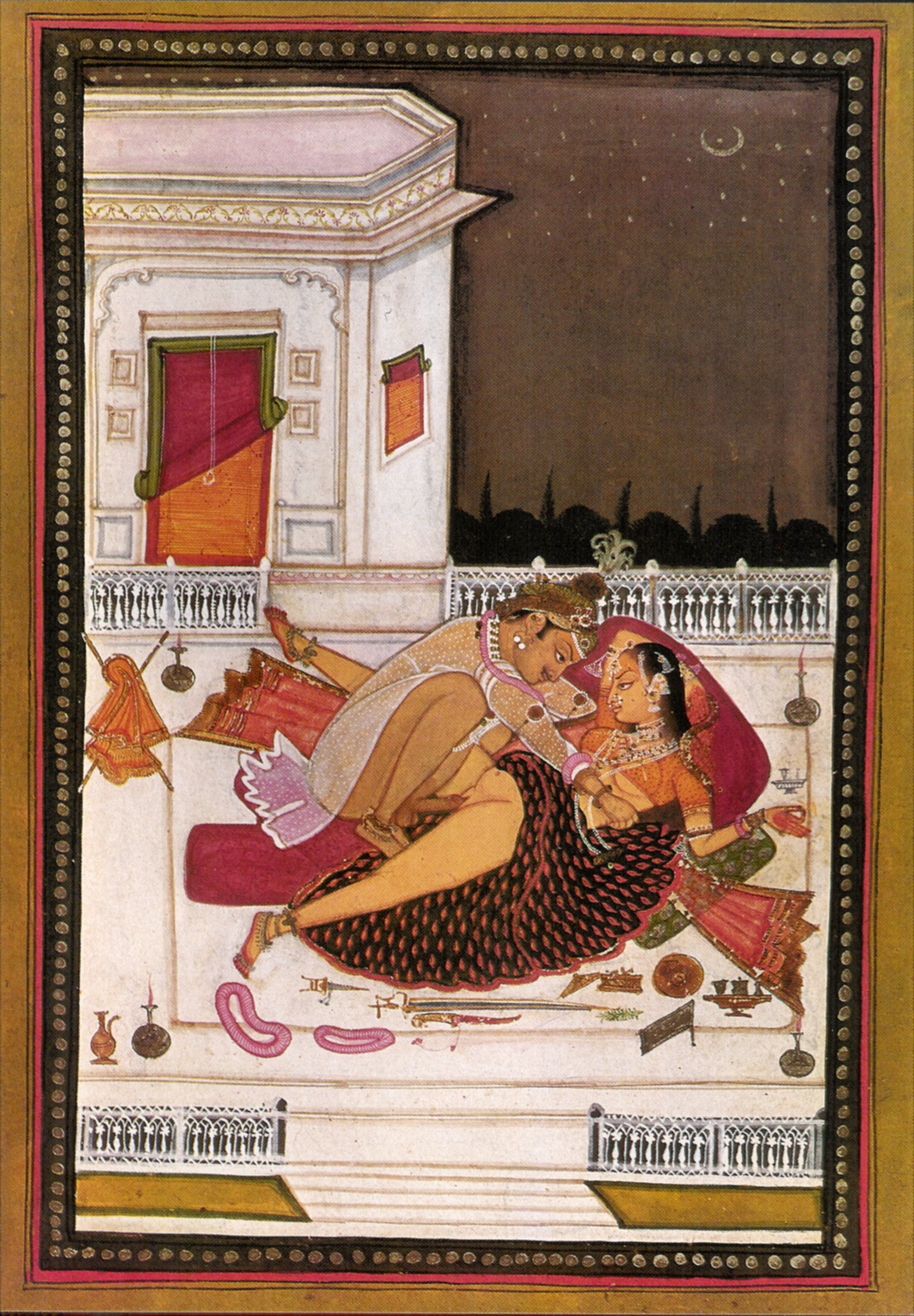

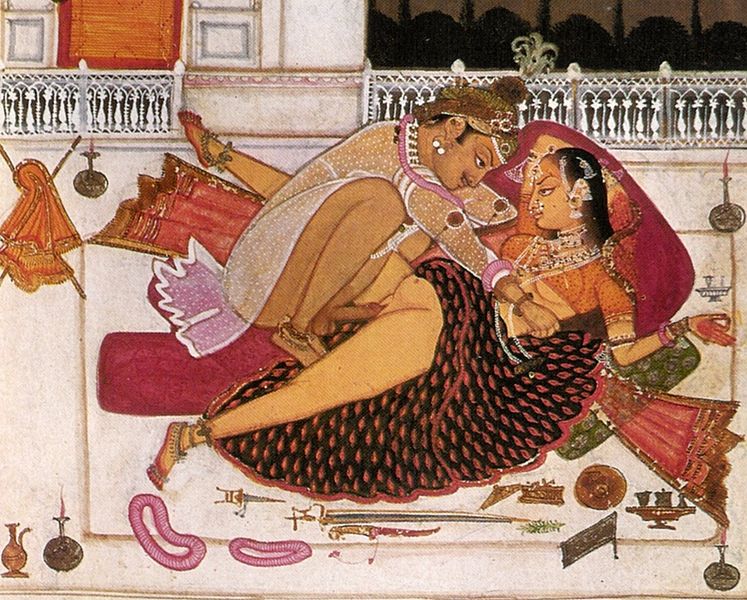

Artistic depiction of a sex position Kama Sutra Illustration

The Kama Sutra Wikipedia

The Kama Sutra (Sanskrit: कामसूत्र

The Kama Sutra is the oldest and most notable of a group of texts known generically as Kama Shastra (Sanskrit: Kāma Śāstra).[6] Traditionally, the first transmission of Kama Shastra or "Discipline of Kama" is attributed to Nandi the sacred bull, Shiva's doorkeeper, who was moved to sacred utterance by overhearing the lovemaking of the god and his wife Parvati and later recorded his utterances for the benefit of mankind.[7]

Historians attribute Kamasutra to be composed between 400 BCE and 200 CE.[8] John Keay says that the Kama Sutra is a compendium that was collected into its present form in the 2nd century CE.[9]

Content

Vatsyayana's Kama Sutra has 1250 verses, distributed in 36 chapters, which are further organized into 7 parts.[10] According to both the Burton and Doniger[11] translations, the contents of the book are structured into 7 parts like the following:

1. General remarks: 5 chapters on contents of the book, three aims and priorities of life, the acquisition of knowledge, conduct of the well-bred townsman, reflections on intermediaries who assist the lover in his enterprises.

2. Amorous advances/Sexual union: 10 chapters on stimulation of desire, types of embraces, caressing and kisses, marking with nails, biting and marking with teeth, on copulation (positions), slapping by hand and corresponding moaning, virile behavior in women, superior coition and oral sex, preludes and conclusions to the game of love. It describes 64 types of sexual acts.

3. Acquiring a wife: 5 chapters on forms of marriage, relaxing the girl, obtaining the girl, managing alone, union by marriage.

4. Duties and privileges of the wife: 2 chapters on conduct of the only wife and conduct of the chief wife and other wives.

5. Other men's wives: 6 chapters on behavior of woman and man, how to get acquainted, examination of sentiments, the task of go-between, the king's pleasures, behavior in the women's quarters.

6. About courtesans: 6 chapters on advice of the assistants on the choice of lovers, looking for a steady lover, ways of making money, renewing friendship with a former lover, occasional profits, profits and losses.

7. Occult practices: 2 chapters on improving physical attractions, arousing a weakened sexual power.

Pleasure and spirituality

Some Indian philosophies follow the "four main goals of life",[12][13] known as the purusharthas:[14]

- Dharma: Virtuous living.

- Artha: Material prosperity.

- Kama: Aesthetic and erotic pleasure.[15][16]

- Moksha: Liberation.

"Dharma is better than Artha, and Artha is better than Kama. But Artha should always be first practised by the king for the livelihood of men is to be obtained from it only. Again, Kama being the occupation of public women, they should prefer it to the other two, and these are exceptions to the general rule." (Kama Sutra 1.2.14)[17]Of the first three, virtue is the highest goal, a secure life the second and pleasure the least important. When motives conflict, the higher ideal is to be followed. Thus, in making money virtue must not be compromised, but earning a living should take precedence over pleasure, but there are exceptions.

In childhood, Vātsyāyana says, a person should learn how to make a living; youth is the time for pleasure, and as years pass one should concentrate on living virtuously and hope to escape the cycle of rebirth.[18]The Kama Sutra acknowledges that the senses can be dangerous: 'Just as a horse in full gallop, blinded by the energy of his own speed, pays no attention to any post or hole or ditch on the path, so two lovers, blinded by passion, in the friction of sexual battle, are caught up in their fierce energy and pay no attention to danger'(2.7.33).

Also the Buddha preached a Kama Sutra, which is located in the Atthakavagga (sutra number 1). This Kama Sutra, however, is of a very different nature as it warns against the dangers that come with the search for pleasures of the senses.

Many in the Western world wrongly consider the Kama Sutra to be a manual for tantric sex.[citation needed] While sexual practices do exist within the very wide tradition of Hindu Tantra, the Kama Sutra is not a Tantric text, and does not touch upon any of the sexual rites associated with some forms of Tantric practice.

Translations

The most widely known English translation of the Kama Sutra was privately printed in 1883. It is usually attributed to renowned orientalist and author Sir Richard Francis Burton, but the chief work was done by the pioneering Indian archaeologist, Bhagwanlal Indraji, under the guidance of Burton's friend, the Indian civil servant Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, and with the assistance of a student, Shivaram Parshuram Bhide.[19] Burton acted as publisher, while also furnishing the edition with footnotes whose tone ranges from the jocular to the scholarly. Burton says the following in its introduction:

It may be interesting to some persons to learn how it came about that Vatsyayana was first brought to light and translated into the English language. It happened thus. While translating with the pundits the 'Anunga Runga, or the stage of love', reference was frequently found to be made to one Vatsya. The sage Vatsya was of this opinion, or of that opinion. The sage Vatsya said this, and so on. Naturally questions were asked who the sage was, and the pundits replied that Vatsya was the author of the standard work on love in Sanskrit literature, that no Sanscrit library was complete without his work, and that it was most difficult now to obtain in its entire state. The copy of the manuscript obtained in Bombay was defective, and so the pundits wrote to Benares, Calcutta and Jaipur for copies of the manuscript from Sanskrit libraries in those places. Copies having been obtained, they were then compared with each other, and with the aid of a Commentary called 'Jayamanglia' a revised copy of the entire manuscript was prepared, and from this copy the English translation was made. The following is the certificate of the chief pundit:

'The accompanying manuscript is corrected by me after comparing four different copies of the work. I had the assistance of a Commentary called "Jayamangla" for correcting the portion in the first five parts, but found great difficulty in correcting the remaining portion, because, with the exception of one copy thereof which was tolerably correct, all the other copies I had were far too incorrect. However, I took that portion as correct in which the majority of the copies agreed with each other.'In the introduction to her own translation, Wendy Doniger, professor of the history of religions at the University of Chicago, writes that Burton "managed to get a rough approximation of the text published in English in 1883, nasty bits and all". The philologist and Sanskritist Professor Chlodwig Werba, of the Institute of Indology at the University of Vienna, regards the 1883 translation as being second only in accuracy to the academic German-Latin text published by Richard Schmidt in 1897.[20]

A noteworthy translation by Indra Sinha was published in 1980. In the early 1990s its chapter on sexual positions began circulating on the internet as an independent text and today is often assumed to be the whole of the Kama Sutra.[21]

Alain Daniélou contributed a noteworthy translation called The Complete Kama Sutra in 1994.[22] This translation, originally into French, and thence into English, featured the original text attributed to Vatsyayana, along with a medieval and a modern commentary. Unlike the 1883 version, Alain Daniélou's new translation preserves the numbered verse divisions of the original, and does not incorporate notes in the text. He includes English translations of two important commentaries:

- The Jayamangala commentary, written in Sanskrit by Yashodhara during the Middle Ages, as page footnotes.

- A modern commentary in Hindi by Devadatta Shastri, as endnotes.

An English translation by Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar, an Indian psychoanalyst and senior fellow at Center for Study of World Religions at Harvard University, was published by Oxford University Press in 2002. Doniger contributed the Sanskrit expertise while Kakar provided a psychoanalytic interpretation of the text.[25]

See also

- Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Kama Sutra

- History of sex in India

- Kamashastra

- Khajuraho Group of Monuments

- Lazzat Un Nisa

- List of Indian inventions and discoveries

- Song of Songs

- The Perfumed Garden

Notes

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (2003). Kamasutra - Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. p. i. ISBN 978-0-19-283982-4. "The Kamasutra is the oldest extant Hindu textbook of erotic love. It was composed in Sanskrit, the literary language of ancient India, probably in North India and probably sometime in the third century"

- ^ Coltrane, Scott (1998). Gender and families. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8039-9036-4.

- ^ Common misconceptions about Kama Sutra. "The Kama Sutra is neither exclusively a sex manual nor, as also commonly used art, a sacred or religious work. It is certainly not a tantric text. In opening with a discussion of the three aims of ancient Hindu life – dharma, artha and kama – Vatsyayana's purpose is to set kama, or enjoyment of the senses, in context. Thus dharma or virtuous living is the highest aim, artha, the amassing of wealth is next, and kama is the least of three." —Indra Sinha.

- ^ Carroll, Janell (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3.

- ^ Devi, Chandi (2008). From Om to Orgasm: The Tantra Primer for Living in Bliss. AuthorHouse. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-4343-4960-6.

- ^ For Kama Sutra as the most notable of the kāma śhāstra literature see: Flood (1996), p. 65.

- ^ For Nandi reporting the utterance see: p. 3. Daniélou, Alain. The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text. Inner Traditions: 1993. ISBN 0-89281-525-6.

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=V9Y_tQfm_WgC&pg=PA21

- ^ For the Kama Sutra as a compilation, and dating to second century CE, see: Kkgeay, pp. 81, 103.

- ^ book, see index pages by Wendy Doniger, also translation by Burton

- ^ Date checked: 29 March 2007 Burton and Doniger

- ^ For the Dharma Śāstras as discussing the "four main goals of life" (dharma, artha, kāma, and moksha) see: Hopkins, p. 78.

- ^ For dharma, artha, and kama as "brahmanic householder values" see: Flood (1996), p. 17.

- ^ For definition of the term पुरुष-अर्थ (puruṣa-artha) as "any of the four principal objects of human life, i.e. धर्म (dharma), अर्थ (artha), काम (kāma), and मोक्ष (mokṣa)" see: Apte, p. 626, middle column, compound #1.

- ^ For kāma as one of the four goals of life (kāmārtha) see: Flood (1996), p. 65.

- ^ For definition of kāma as "erotic and aesthetic pleasure" see: Flood (1996), p. 17.

- ^ Quotation from the translation by Richard Burton taken from [1]. Text accessed 3 April 2007.

- ^ Book I, Chapter ii, Lines 2-4 Vatsyayana Kamasutram Electronic Sanskrit edition: Titus Texts, University of Frankfurt bālye vidyāgrahaṇādīn arthān, kāmaṃ ca yauvane, sthāvire dharmaṃ mokṣaṃ ca

- ^ McConnachie (2007), pp. 123–125.

- ^ McConnachie (2007), p. 233.

- ^ Sinha, p. 33.

- ^ The Complete Kama Sutra by Alain Daniélou

- ^ Stated in the translation's preface

- ^ Balagangadhara, S.N (2007). Antonio De Nicholas, Krishnan Ramaswamy, Aditi Banerjee. ed. Invading the Sacred. Rupa & Co. pp. 431–433. ISBN 978-81-291-1182-1.

- ^ McConnachie (2007), p. 232.

References

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4. (fourth revised & enlarged edition).

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9.

- Daniélou, Alain (1993), The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Translation of the Classic Indian Text, Inner Traditions, ISBN 0-89281-525-6.

- Sudhir Kakar and Doniger, Wendy (2002), Kamasutra (Oxford World's Classics), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283982-9.

- Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

- Flood, Gavin (Editor) (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5.

- Hopkins, Thomas J. (1971). The Hindu Religious Tradition. Cambridge: Dickenson Publishing Company, Inc..

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- McConnachie, James (2007). The Book of Love: In Search of the Kamasutra. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-373-2.

- Sinha, Indra (1999). The Cybergypsies. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-600-34158-5.

External links

- Find more about Kama Sutra at Wikipedia's sister projects

- Definitions and translations from Wiktionary

- Media from Commons

- Learning resources from Wikiversity

- News stories from Wikinews

- Quotations from Wikiquote

- Source texts from Wikisource

- Textbooks from Wikibooks

- Sir Richard Burton's English translation on Indohistory.com

- The Kama Sutra in audio format from LibriVox

- The Kama Sutra in the original Sanskrit provided by the TITUS project

- Kama Sutra at Project Gutenberg

Sex manuals

Medieval sex manuals include the lost works of Elephantis, by Constantine the African; Ananga Ranga, a 12th century collection of Hindu erotic works; and The Perfumed Garden for the Soul's Recreation, a 16th century Arabic work by Sheikh Nefzaoui. The fifteenth-century Speculum al foderi (The Mirror of Coitus) is the first medieval European work to discuss sexual positions. Constantine the African also penned a medical treatise on sexuality, known as Liber de coitu.

Elephantis Wikipedia

Elephantis (fl. late 1st c. BC) was a Greek poetess apparently renowned in the classical world as the author of a notorious sex manual. Her works have not survived.

Works

According to Suetonius, the Roman Emperor Tiberius took a complete set of her works with him when he retreated to his resort on Capri.[1]

One of the poems in the Priapeia refers to her books:

- Obscenas rigido deo tabellas

dicans ex Elephantidos libellis

dat donum Lalage rogatque, temptes,

si pictas opus edat ad figuras.[2]

And an epigram by the Roman poet Martial, which Smithers and Burton included in their collection of poems concerning Priapus, wrote:

- Quales nec Didymi sciunt puellae,

Nec molles Elephantidos libelli,

Sunt illic Veneris novae figurae[4]

She also wrote a manual about cosmetics and another about abortives.[5]

Notes

- ^ Suet. Tib. 43.2.

- ^ Priapeia 4.

- ^ a b Trans. L.C. Smithers and R.F. Burton, Priapea sive diversorum poetarum in Priapum lusus, or, Sportive Epigrams on Priapus (1890).

- ^ Martial, Ep. 43.1–4.

- ^ Plant. p. 118.

- Ian Michael Plant (2004). Women writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: an anthology. University of Oklahoma Press.

Ananga Ranga, Wikipedia

The Ananga Ranga (Stage of Love) or Kamaledhiplava (Boat in the Sea of Love) is an Indian sex manual written by Kalyana malla in the 15th or 16th century.[citation needed] The poet wrote the work in honor of Lad Khan, son of Ahmed Khan Lodi. He was related to the Lodi dynasty, which from 1451 to 1526 ruled from Delhi.[1] Later commentators have said it is aimed specifically at preventing the separation of a husband and wife. This work is often compared to the Kama Sutra, on which it draws.

Overview

It was translated into English in the year 1885, under the editorship of Sir Richard Francis Burton and consequently burnt by his wife Isabel Burton in the weeks following his death.

"Satisfaction and enjoyment comes for a man with possession of a beautiful woman. Men marry because of the peaceful gathering, love, and comfort and they often get nice and attractive women. But the men do not give the women full satisfaction The reason is due to the ignorance of the writings of the Kamashastra and the disdain of the different types of women. These men view women only from the perspective of an animal. They are foolish and spiritless".[2]

The work was intended to show that a woman is enough for a man. The book provides instructions in how a husband can promote the love for his wife through sexual pleasure. The husband can so greatly enjoy living with his wife, that it is as if he had lived with 32 different women. The increasingly varied sexual pleasures are able to produce harmony, thus preventing the married couple from getting tired of one another. In addition to the extensive catalogue of sexual positions for both partners, there are details regarding foreplay and lure.

The contents of the chapters of Burton's translation of the Ananga Ranga are as follows:

- Chapter I: considers the four classes of women

- Chapter II: Of the Various Seats of Passion in Women

- Chapter III: Of the Different Kinds of Men and Women

- Chapter IV: Description of the General Qualities, Characteristics, Temperaments, Etc., of Women.

- Chapter V: Characteristics of the Women of Various Lands

- Chapter VI: Treating of Vashikarana

- Chapter VII: Of Different Signs in Men and Women

- Chapter VIII: Treating of External Enjoyments

- Chapter IX: Treating of Internal Enjoyments in Its Various Forms

- Appendix I: Astrology in Connection With Marriage

- Appendix II: (considers a variety of alchemical recipes, which are either potentially lethal, or completely ineffective as a remedy, or both)

External links

Ratirahasya Wikipedia

The Ratirahasya (Sanskrit रतिरहस्य ) (translated in English as Secrets of Love, also known as the Koka Shastra) is a medieval Indian sex manual written by Kokkoka, a poet, who is variously described as Koka or Koka Pundit.[1][2][3][4] The exact date of its writing is not known, but it is estimated the text was written in the 11th or 12th century.[2] It is speculated that Ratirahasya was written to please a king by the name Venudutta. Kokkoka describes himself in the book as siddha patiya pandita, i.e. "an ingenious man among learned men".[1][5] The manual was written in Sanskrit.[6]

Unlike the Kama Sutra, which is an ancient sex manual related to Hindu literature, Ratirahasya deals with medieval Indian society. During the medieval age, India became more conservative compared to ancient India, freedom of women decreased, and premarital and extramarital sex were frowned upon. A sex manual was needed that would be suitable for the medieval cultural climate, and Ratirahasya was written, quite different from the ancient text Kama Sutra.[2]

There are fifteen pachivedes (chapters) and 800 verses in Ratirahasya which deal with various topics such as different physiques, lunar calendar, different types of genitals, characteristics of women of various ages, hugs, kisses, sexual intercourse and sex positions, sex with a strange woman, etc.[1][2] Kokokka describes various stages of love in Ratirahasya, the fifth stage being weight loss, the ninth is fainting, and the tenth and last stage is death.[7] Ratirahasya makes classifications of women, and describes erogenous zones and days that lead to women's easy arousal.

Ratirahasya is the first book to describe in detail Indian feminine beauty. The book classified women into four psycho-physical types, according to their appearance and physical features.[8][9]

- Padmini (lotus woman)

- Chitrini (art woman)

- Shankini (conch woman)

- Hastini (elephant woman)

According to W. G. Archer, Kokkoka "is concerned with how to make the most of sex, how to enjoy it and how to keep a woman happy."[2] In writing this text, Kokokka depended on a number of other authors including, among others Nandikeshvara, Gonikaputra, and Vatsyayana.[11]

Arabic, Persian and Turkish translations of the book are entitled Lizzat-al-Nissa.[12] Alex Comfort, author of The Joy of Sex, made an English translation of Ratirahasya in 1964 titled The Koka Shashtra, Being the Ratirahasya of Kokkoka, and Other Medieval Indian Writings on Love (London: George Allen and Unwin). Another English translation was made by S. C. Upadhyaya, entitled Kokashastra (Rati Rahasya) of Pundit Kokkoka. Some commentaries have been written on this text by Avana Rama Chandra, Kavi Prabhu, and Harihara. It is a popular text in India, second only to the Kama Sutra among sex manuals.[11]

References

- ^ a b c Vātsyāyana; Lance Dane (7 October 2003). The Complete Illustrated Kama Sutra. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-89281-138-0. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Suzanne G. Frayser; Thomas J. Whitby (1995). Studies in Human Sexuality: a selected guide. Libraries Unlimited. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-56308-131-6. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (2008). Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions. ABC-CLIO. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-85109-980-1. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Krishan Lal Kalia (1 January 1997). Eminent Personalities of Kashmir. Discovery Publishing House. p. 16. ISBN 978-81-7141-345-4. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Ra, Frank. Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana. Subjective Well-being Institute.

- ^ David Goodway (1 November 2011). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. PM Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-1-60486-221-8. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Siegfried Lienhard (1984). A History of Classical Poetry: Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 119. ISBN 978-3-447-02425-9. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Kazmi, Nikhat (Jun 7, 2004). "Our B-I-G fix". Times of India. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Molly Oldfield; John Mitchinson (21 Apr 2011). "QI: Quite interesting facts about weddings" (in English). The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Kar (1 January 2005). Comprehensive Textbook of Sexual Medicine. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 456. ISBN 978-81-8061-405-7. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b Dge-ʼdun-chos-ʼphel (A-mdo) (1992). Tibetan arts of love. Snow Lion Publications. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-937938-97-3. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night. Forgotten Books. ISBN 1440039984, 9781440039980.

Modern sex manuals

Despite the existence of ancient sex manuals in other cultures, sex manuals were banned in Western culture for many years. What sexual information was available was generally only available in the form of illicit pornography or medical books, which generally discussed either sexual physiology or sexual disorders. The authors of medical works went so far as to write the most sexually explicit parts of their texts in Latin, so as to make them inaccessible to the general public (see Krafft-Ebing's Psychopathia Sexualis as an example).A few translations of the ancient works were circulated privately, such as The Perfumed Garden….

In the late 19th Century, Ida Craddock wrote many serious instructional tracts on human sexuality and appropriate, respectful sexual relations between married couples. Among her works were The Wedding Night and Right Marital Living. In 1918 Marie Stopes published Married Love, considered groundbreaking despite its limitations in details used to discuss sex acts.

Theodoor Hendrik van de Velde's book Het volkomen huwelijk (The Perfect Marriage), published in 1926, was well known in Netherlands, Germany, Sweden and Estonia. In Germany, Die vollkommene Ehe reached its 42nd printing in 1932 despite its being placed on the list of forbidden books, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, by the Roman Catholic Church. In Sweden, Det fulländade äktenskapet was widely known although regarded as pornographic and unsuitable for young readers long into the 1960s. In English, Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique has 42 printings in its original 1930 edition, and was republished in new editions in 1965 and 2000.

David Reuben, M. D.'s book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), published in 1969, was one of the first sex manuals that entered mainstream culture in the 1960s. Although it did not feature explicit images of sex acts, its descriptions of sex acts were unprecedentedly detailed, addressing common questions and misunderstandings Reuben had heard from his own patients. Most notably, Reuben dismissed popular medical-psychiatric notions of "vaginal" vs. "clitoral" orgasm, explaining exactly how female physiology works.

The Joy of Sex by Dr. Alex Comfort was the first visually explicit sex manual to be published by a mainstream publisher. Its appearance in public bookstores in the 1970s opened the way to the widespread publication of sex manuals in the West. As a result, hundreds of sex manuals are now available in print.

One of the currently most well known in America is The Guide to Getting it On by Paul Joannides. Now in its sixth edition, it has won several prestigious awards and been translated into 12 foreign languages since appearing in 1996.[1]

Notes and references

- ^ Joannides, Paul (2006), The Guide To Getting It On (fifth ed.), Oregon, USA: Goofy Foot Press, ISBN 1-885535-69-4.

- "4, Sexual Eruption and the Reaction: The Interwar Years", Teaching America About Sex: marriage guides and sex manuals from the late Victorians to Dr. Ruth, NYU Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-8147-5532-7.

- "Sex Manuals", American Memory, Library of Congress.